Early Pan-African Roots

Delegates at the Second Pan-African Congress in Brussels (1921), an early gathering of African and diaspora leaders pushing for unity.

In the early 20th century, Black intellectuals and activists from Africa and its diaspora began meeting to demand an end to colonial rule. They believed in a shared destiny: as one historian notes, Pan-Africanism rested on the idea that “the destinies [of Africa’s peoples] are interconnected”. By 1921, delegates from dozens of African nations and the diaspora gathered in Brussels (pictured above) to strategize for liberation. The idea of a united Africa even cropped up in poetry: Jamaican activist Marcus Garvey wrote a poem in 1924 titled “Hail! United States of Africa,” imagining a grand continental federation long before colonialism ended.

Nkrumah’s Vision of Unity

Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s independence leader and a leading Pan-Africanist, championed a united Africa decades ago.

After Ghana’s independence in 1957, President Kwame Nkrumah pushed the idea of an African federation as the logical next step. In 1958 he announced his bold vision of a “United States of Africa” at a continent-wide conference. Nkrumah argued that a single government – modeled loosely on the USA – was needed to make African nations strong and secure. Inspired by his rhetoric, a bloc of states including Ghana, Ethiopia and Egypt convened in 1963 to form the Organization of African Unity (OAU). The OAU’s charter famously pledged to “promote the unity and solidarity of the African States” while also pledging to “defend their sovereignty” (reflecting the tension between union and independence).

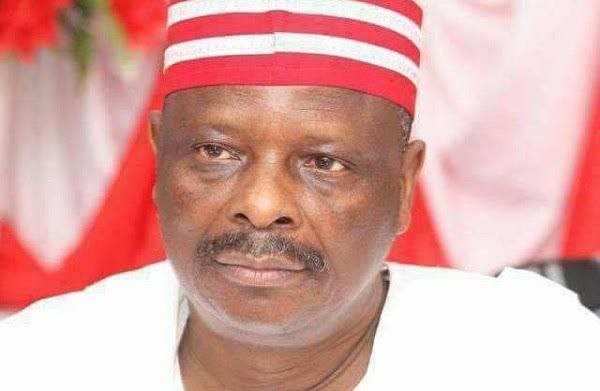

Gaddafi’s Pan-African Ambitions

In the late 20th century, Libya’s leader Muammar Gaddafi became the most vocal advocate of the idea. At a summit in Sirte in 1999 he presented a visionary plan: a borderless United States of Africa “ruled by one government under a single president” with a unified army and economy. When Gaddafi became chair of the African Union in 2009 he reiterated this goal, saying he would “continue to insist that our sovereign countries work to achieve the United States of Africa”. He even outlined plans for a single African currency, common defense force and one continental passport, backing these proposals with billions of dollars of Libyan aid (paying other countries’ AU dues and funding development).

However, Gaddafi’s ambitions ran into resistance. Many leaders were wary of ceding power: at that 2009 meeting, Tanzania’s president explained that “the ultimate is the United States of Africa,” but said there were intermediate “building blocks” needed to reach that goal. In practice, Gaddafi’s vision “never found the resounding support it needed”, and by the time of Libya’s 2011 upheaval the federation project had stalled.

Motivations for a United Africa

- Shared identity: Pan-Africanists long argued that Africans share a common history, culture and destiny. This sense of unity drove many to seek one nation.

- Ending colonialism: African leaders believed that a united front was needed to overthrow imperialism. As early as 1958, activists called on all Africans to unite in the fight against colonial rule.

- Political strength: A federation could amplify Africa’s global influence. Gaddafi insisted that a united state was “the only way Africa can develop without Western interference”.

- Economic and security benefits: Proponents envisioned a common market, currency and defense. Gaddafi even floated the idea of one African currency and free movement with a single passport, arguing it would boost trade and continental solidarity.

- Symbolic pride: Finally, uniting under one flag would fulfill a symbolic dream of African renaissance – echoing historic examples like Haiti’s 1804 independence or the great empires of pre-colonial Africa.

Challenges to a United Africa

- Sovereignty fears: After independence, most governments clung to their hard-won autonomy. Many leaders quickly deemed federation “impractical” since it might infringe on national sovereignty.

- Political divisions: Even in the 1960s, African states split over unity. The 1961 Casablanca Group (Ghana, Guinea, etc.) pushed for rapid political union, while the rival Monrovia Group (Liberia, Ivory Coast, etc.) preferred only loose cooperation.

- Step-by-step approach: Many countries favored strengthening regional blocs before full union. In 2009 Tanzania’s president stressed that ‘there are building blocks’ toward unity, implying that a United States of Africa would be a long-term goal.

- Limited commitment: In practice, few leaders made binding moves toward a single state. Gaddafi’s grand vision often won applause in speeches, but was met mostly with “lip service” when it came to concrete action.

- Practical hurdles: Africa’s diversity poses real obstacles. With over 50 nations speaking hundreds of languages and existing colonial borders, merging all governments, economies and armies into one super-state is an enormously complex task.

Legacy and Outlook

The United States of Africa remains more a potent ideal than a reality today. The African Union now focuses on cooperation and gradual integration (such as continental trade deals, shared infrastructure and passport-free travel) rather than an immediate political merger. As one review noted, Gaddafi’s dream “never found the resounding support it needed”. Still, the vision of a united continent continues to inspire activists and thinkers. From Garvey and Nkrumah to modern Pan-African movements, the idea of a single African nation survives in discourse. For now, it serves as a powerful symbol of solidarity and a guiding star in Africa’s ongoing quest for unity and self-determination.

Be the first to leave a comment